const - JS | lectureJavaScript OOP

Inheritance Between "Classes" - Constructor Functions

Over the last couple of lectures, we explored how prototypal inheritance works in JavaScript. And we did that using a couple of different techniques: constructor functions, ES6 classes, and the Object.create method. All of these techniques basically allow objects to inherit methods from its prototype. But now let's turn our attention to more real inheritance, like we learned in the very first lecture of this section.

When I say real inheritance, I mean inheritance between classes and not just prototypal inheritance between instances and a prototype property like we've been doing so far. And note that I'm using the class terminology here because it simply makes it easier to understand what we will do. But, of course, we already know that real classes do not exist in JavaScript.

In this lecture, we will create two new classes: Employee and Engineer. And we will make the Engineer class inherit from the Employee class. So, the Engineer class will be the parent class, and the Employee class will be the child class. That's because Engineer is basically a subtype of Employee.

This is really useful because, with this inheritance setup, we can have specific methods for an Engineer, but then the Engineer can also use generic methods from the Employee class. And that's basically the idea of inheritance that we will implement in this lecture.

Just like before, we will start by implementing this using constructor functions. It might feel a bit difficult to understand at first, but I promise you that it will get easier as we go along. This will allow you to understand exactly how we set up the prototype chain in order to allow inheritance between the prototype properties of two different constructor functions. Then in the next lecture, we will do the same thing using ES6 classes, which, as you would expect, is a lot easier. And finally, of course, we will go back to using the Object.create method as well.

So, let's get started. First, let's create our parent Employee constructor function. This parent class will have the properties name, dateOfBirth, department, and a calculateAge method added to its prototype property.

const Employee = function (name, dateOfBirth, department) {

this.name = name; this.dateOfBirth = dateOfBirth; this.department = department;};

Employee.prototype.calculateAge = function () {

console.log(2022 - this.dateOfBirth);

};Now, let's create our child Engineer constructor function. Usually, we want a child class to have the same functionality as the parent class but with some additional functionality. Hence, we usually pass on the same arguments and some additional ones.

const Engineer = function (name, dateOfBirth, department, projects, position) {

this.name = name; this.dateOfBirth = dateOfBirth; this.department = department; this.projects = projects;

this.position = position;

};Let's now create a new engineer object.

const johnson = new Engineer(

'Shawn Johnson',

1990,

'Engineering',

['Microservices', 'Security'],

'Senior Engineer'

);

console.log(johnson);

Let's now add a method to our Enginner prototype property called present.

Engineer.prototype.present = function () {

console.log(

`Hello, my name is ${this.name}. I am a ${this.position} in the ${this.department} department.`

);

};Let's now call the present method on our johnson object and see what happens.

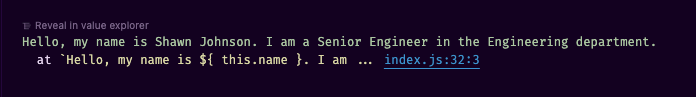

johnson.present();

It works great! However, there is one thing that we can and should improve in our Engineer constructor function. Right now, the above-highlighted section in the Engineer constructor function is basically a simple copy of the Employee constructor function. And as you know, having duplicate code is never a good idea. First, because it violates the DRY principle, and second and even worse, imagine that the implementation of the Employee constructor function changes in the future, then that change will not be reflected in the Engineer constructor function.

So instead of having the duplicate code, let's simply call the Employee function from within the Engineer function and pass in the arguments.

const Engineer = function (name, dateOfBirth, department, projects, position) {

Employee(name, dateOfBirth, department); this.projects = projects;

this.position = position;

};Do you think this will work? Let's try it out.

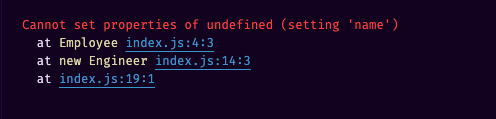

Arggh! We get an error 🫤. The reason why we are getting this error is because we are now calling the Employee function as a regular function. And remember that the this keyword inside a regular function call is set to undefined. Hence that's why we get the above error.

So instead of simply calling the Employee function, we need to manually set the this keyword as well. So do you remember how we can call a function and at the same time set the this keyword inside that function? Well, we can simply use the call method. So let's do that.

const Engineer = function (name, dateOfBirth, department, projects, position) {

/** * 1. new Engineer(...) creates a new empty object * 2. The this keyword inside the Employee Engineer call is set to that empty object * 3. The this keyword is passed to the Employee function as the first argument of the call method * 4. The Employee function then sets the properties on the empty object */ Employee.call(this, name, dateOfBirth, department); this.projects = projects;

this.position = position;

};If you now execute your code again, you will see that it works perfectly fine. Hence, this is a much better and more robust solution.

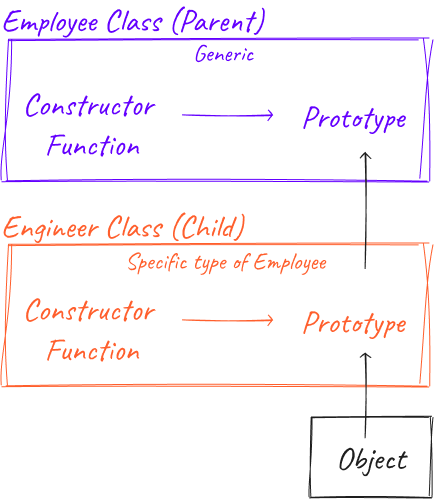

So far, this is what we have built:

It's simply the Engineer constructor function, its prototype property, and then the johnson object linked to its prototype. And that prototype is, of course, the constructor function's prototype property. Now, this link between instance and prototype has been made automatically by creating the johnson object using the new keyword. All of this is what we've already learned, so there is nothing new at this point.

Now, an engineer is also an employee. So we want Engineer and Employee to be connected like this:

So we want the Engineer class to be the child class and inherit from the person class, which will then function as the parent class. This way, all instances of Engineer could also get access to methods from the Employee prototype property, like the calculateAge method, through the prototype chain. And that's the whole idea of inheritance.

Looking at the above diagram, basically what we want to do is to make Employee.prototype the prototype of Engineer.prototype. Or in other words, we want to set the __proto__ property of Engineer.prototype to Employee.prototype.

We will have to create this connection manually. And to do this we will have to use the Object.create method. Because defining prototypes manually is exactly what Object.create does. Enough talking, let's do it.

/**

* Make sure to write the below-highlighted code before the present method declaration.

* I will explain why later.

*/

const Engineer = function (name, ...) {/**/};

Engineer.prototype = Object.create(Employee.prototype);

Engineer.prototype.present = function () {

/**/

};With this, the Engineer.prototype object is now an object that inherits from Employee.prototype. Now, the reason I asked you to create this connection before adding any method to the Engineer.prototype object is because, Object.create will return an empty object. Hence, at the moment we create this connection, the Engineer.prototype object is empty. And so then, on to that empty object, we can add methods like the present method.

Whereas, if we did it the other way around, and added the present method to the Engineer.prototype object first, then the Object.create method would basically overwrite the present method.

Now you might be wondering why we even needed to use the Object.create method in the first place? Why couldn't we simply write the following code?

Engineer.prototype = Employee.prototype;This seems logical, but it will not work because if we do this, we will end up with the following:

The image on the right is the result of the above code. It is a completely wrong prtototype chain. It is because we are actually saying that the Employee prototype property and the Engineer prototype property should be the same object. And that's not what we want. We want the Engineer prototype object to be the prototype of Employee.prototype. So, we want to inherit from it, but it should not be the same object. And that's exactly why we need to use the Object.create method.

With all this in place, we should be able to use the calculateAge method on the johnson object.

johnson.calculateAge(); // 32Let's now analyze what exactly happened here...

We already know that this worked because of the prototype chain. But let's see exactly how from the below diagram.

From the diagram, when we do johnson.calculateAge(), we are effectively doing a property or method lookup. In this case, as we know, the calculateAge method is not directly on the johnson object. It is also not on johnson's prototype because that's where we defined the present method and not the calculateAge method. So, just like before, whenever we try to access a method that's not on the object's prototype, JavaScript will go up the prototype chain and look for it. And that's exactly what happened here. JavaScript will finally find the calculateAge method in Employee.prototype, which is exactly where we defined it.

That's the whole reason why we set up the prototype chain like this. So that the johnson object can inherit whatever methods are in its parent's class. In summary, we are now able to call a method that is on an Employee prototype property on an Engineer object, and it still works.

Still, from the diagram, we can see that Object.prototype sits at the top of the prototype chain. And this means that we could still call a method that is on the Object.prototype property on the johnson object. For example, we could call the hasOwnProperty method. It doesn't matter how far away in the prototype chain a method is.

To finish this lecture, let's now check all we just said above.

Let's start by checking the __proto__ property of the johnson object.

console.log(johnson.__proto__);

We can see that the __proto__ property of the johnson object is the Engineer.prototype object.

We can clearly see that it contains the present method. But also, it says it's of type Employee instead of Engineer. We will fix this later.

Let's move up one step further again and check __proto__.__proto__.

console.log(johnson.__proto__.__proto__);

We indeed get the Employee.prototype object which contains the calculateAge method.

Let's now fix the __proto__ property of the johnson object. Ideally, checking Engineer.prototype.constructor should point back to the Engineer function. But it doesn't. It points to the Employee function. So, we need to fix this.

console.dir(Engineer.prototype.constructor); // EmployeeThe reason we are having this is because we set the prototype property of Engineer using the Object.create method. Hence, this makes that the constructor of Engineer.prototype is still Employee. We need to fix this because, sometimes, it is important to rely on the constructor property.

To fix this, all we have to do is to set the constructor property to Engineer.

Engineer.prototype.constructor = Engineer;