const - JS | lectureJavaScript OOP

Prototypal Inheritance and the Prototype Chain

In this lecture, we will consolidate the knowledge we got from the two previous lectures in a nice diagram that brings everything we've learned so far. Everything starts with the Person constructor function that we've been working with.

This constructor function has a prototype property which is an object, and inside that object, we defined the calculateAge method. And Person.prototype actually also has a reference back to Person, which is the constructor property.

However, remember that Person.prototype is NOT the prototype of Person. Instead, it's the prototype of all instances that are created through the Person constructor.

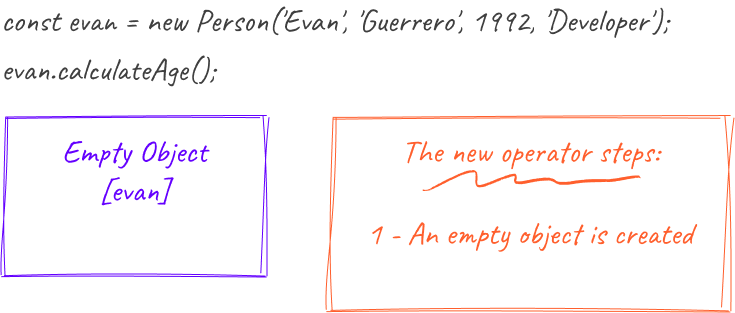

Speaking of instances (objects), let's now analyze how an object is created using the new operator and the constructor function. So, when we call a function, any function with the new operator, the first thing that's going to happen is that a brand new empty object is created instantly.

Then, the this keyword in the function call is set to the newly created object. So, inside the function's execution context, this is now the new empty object. That's why we can now use this to set properties on the object in the constructor function. Because doing so will automatically set the properties on the new empty object.

Next, now comes the magical step. The newly created object is linked to the constructor's prototype property. In this case, Person.prototype. And this happens internally by adding the __proto__ property to the new object.

Finally, the new object is automatically returned from the function unless we explicitly return something else. But in a constructor function like Person, we don't do that. So, with this, the result of the new operator, and the Person constructor function, is a new object we just created programmatically, which is now stored in the evan variable. And this process that we just went through is how it works with function constructors and ES6 classes but not with the Object.create syntax we will use later.

Nice! Let's now move on and answer the questions: Why does it work this way? And why is this technique so powerful and useful? To answer these questions, let's move on to the next line of code where we attempt to call the calculateAge method on the evan object. However, JavaScript cannot find this method on the evan object.

So, what happens now in this situation? Well, If a property or a method cannot be found in a certain object, JavaScript will look in its prototype. And that's how the calculateAge method can run correctly and return a result. And this behavious is what we already called prototypal inheritance or delegation.

So, the evan object inherited the calculateAge method from its prototype. Or in other words, the evan object delegated the calculateAge method to its prototype. And as I already mentioned in one of the previous lectures, the beauty of this is that now we can create as many objects as we want, and they will all inherit the calculateAge method from the Person.prototype object.

Now the fact that evan is connected to a prototype, and the ability of looking up methods and properties in a prototype, is what we call the prototype chain. So, the evan object, and its prototype form a prototype chain. But actually, the prototype chain does not end there; it continues.

Let's get deeper into this ⛏.

From the above image, there is nothing new. Still the same Person constructor function, and its prototype property, and the evanobject linked to its prototype by the __proto__ property. But now, let's remember that Person.prototype is an object, and all objects in JavaScript have a prototype property. Therefore, Person.prototype must also have a prototype. And the prototype of Person.prototype is Object.prototype.

But why is that? Well, Person.prototype is just a simple object, which means, it has been built by the built-in Object constructor function. And this is actually the function that is called behind the scenes whenever we create an object literal (Just an object with curly braces).

WHat matters here is that Person.prototype itself needs to have its prototype. And since it has been created by the Object constructor function, its prototype will be the Object.prototype object. It is the same logic as with the evan object. It has been created by the Person constructor function, and therefore, it has a prototype, which is the Person.prototype object.

This entire series of links between the objects is called the prototype chain. And Object.prototype is usually the top of the prototype chain, which means that its prototype is null, which then marks the end of the prototype chain.

So, in a certain way, the prototype chain is similar to the scope chain but with prototypes. In the scope chain, whenever JavaScript can't find a certain variable in a certain scope, it looks up in the next scope in the scope chain. On the other hand, in the prototype chain, whenever JavaScript can't find a certain property or method in a certain object, it looks up in the next prototype in the prototype chain.

To finish, let's actually see another example of a method lookup. To do that, let's say we call the hasOwnProperty method on the evan object. Just as we saw earlier, JavaScript will start by trying to find the called method on the object itself. But, of course, it can't find the called method on evan. So, according to how the prototype chain works, it will then look into its prototype, which is Person.prototype. However, we didn't define any hasOwnProperty in there either, and so JavaScript will then look into the next prototype in the chain, which is Object.prototype. And Object.prototype, does actually contain a bunch of built-in methods, including the hasOwnProperty method. So, JavaScript will find the method there, and then execute it on the evan object as if it was defined on the evan object itself.

Remember that the method has not been copied to the evan object. Instead, it simply inherited the method from Object.prototype through the prototype chain.